Reese Basses and the AM-GM Inequality

A short experiment in trigonometry and sound design.

background

Reese basses are electronically synthesized bass sounds associated with the drum and bass genre, but are quite popular in virtually every domain of electronic music. A reese bass consists of two (or more) oscillators—usually sawtooth waves—slightly detuned from each other. This detuning causes the two waves to phase in and out, and the resulting sound to wobble in amplitude.

Understanding the cause of this wobble is a simple exercise in trigonometry: when two sine waves of slightly differing frequencies are played back together, they slowly alternate between constructively and destructively interfering, changing the amplitude of the signal. In our analysis of this phenomenon, we can focus our attention on sine waves in particular, since any periodic wave is naturally decomposed into a sum of sine waves by Fourier series.

In fact, the “sum-to-product” identity states that

To interpret this formula in the language of sound, imagine that and are two slightly detuned sound waves, and we are playing them back together (or summing them). The two terms on the right hand side then correspond directly to the “reesing” and audible frequencies of this summed wave: since and are close to each other, the argument of the cosine term is small, representing the wobbling of the wave’s amplitude. Similarly, the sine term, with an argument in between and , represents the actual audible frequency of the sound.

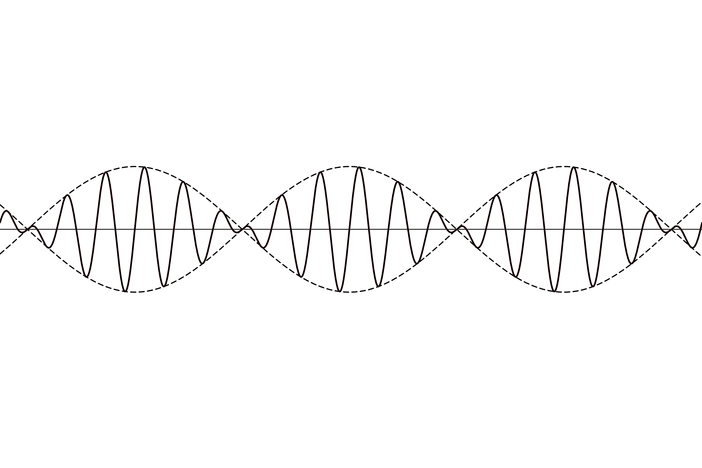

The sum of two detuned sines and the resulting wobble effect. The dotted-line waves represent the low-frequency cosine wobble term, which bounds the higher-frequency signal. Created in Desmos.

the problem

Many years ago, when I was still regularly producing electronic music, I discovered a peculiarity when designing a reese bass of my own. My design used a common technique that modified the pitches of two oscillators by an equal offset both upwards and downwards—for example, one oscillator detuned +10 cents and the other -10 cents. Most software synthesizers don’t give direct control over the frequencies of oscillators; rather, they give control over the oscillators’ pitches.

I wanted the fundamental frequency of the reese bass to be exactly the frequency of the note I played on my keyboard so that it would be in tune with the rest of the song I was composing. However, I noticed that when I increased the two oscillators’ detune amount to make the sound wobble faster, the frequency of the resulting sound was not centered at the target note as desired; rather, it was ever so slightly higher, causing the bass to sound sharp and out of tune.

mathematics

So, why did this happen?

The first thing to understand is that pitch and frequency are related, yet different quantities. When we increase the pitch of a sound by an octave, we multiply its frequency by 2. Similarly, increasing the pitch of a sound by a semitone (in 12-tone equal temperament) multiplies the frequency by . In other words, adding a certain amount to the pitch of a sound multiplies its frequency by a corresponding amount.

Mathematically, we essentially have that

or

(Here, we’re keeping the base of the logarithm, , undefined, since the “formula” doesn’t really account for units of frequency or pitch. This is all very handwavy, but entirely correct in that it communicates the right relationship between pitch and frequency and allows for some nice pseudo-calculations.)

Now, let’s say that we have two oscillators playing at pitches and , and corresponding frequencies and . Their “central” pitch is then given by the arithmetic mean,

following intuition of what the “center” of two pitches should be. Calculating the frequency of this central pitch using our handy (quasi-)formula, we find that

So, we’ve just calculated that the frequency of the central pitch is given by the geometric mean of the two oscillators’ frequencies. You might be able to see where this is going.

back to reeses

We’re now ready to apply everything we’ve learned back to the reese bass. Suppose that we have two sine wave oscillators centered around the pitch and detuned equally up and down by an amount , so that their frequencies are given by

As we calculated above, the frequency of their central pitch is

which should make sense based on our definitions: we’ve detuned the oscillators by the same pitch amount, so their central pitch should just be .

However, the actual frequency of the resulting sound (by playing the two oscillators back together), which we found from the sum-to-product identity as the argument of the sine term, is given by

Here’s where the AM-GM inequality comes in: means the inequality is strict.

So, we’ve proven that the actual, audible frequency of a reese bass created by equal detune amounts is strictly greater than the frequency of the target central pitch. In other words, a reese bass created in this fashion will always be slightly sharp. Admittedly, the amount of detune is very slight, but it’s noticeable when, for example, you want to have a sub bass at the fundamental frequency and end up running into some nasty phasing issues.It’s also not difficult to show that as increases, this tuning error grows.

the solution

We’ve discovered that the limitations of many software synthesizers are unknowingly preventing sound designers from creating perfectly in-tune reese basses. A tragedy, no doubt. To remedy this problem, I’ve developed a small proof-of-concept VST plugin using JUCE that detunes two oscillators by an equal frequency amount rather than pitch amount. As a result, the resulting wave’s fundamental frequency is correctly placed at the arithmetic mean of the two oscillator frequencies, keeping the sound in tune.

A video demonstration of the plugin. The first sound you hear is a reese bass made by detuning by pitch in Serum, and the second is my custom plugin detuning by frequency. The Ableton Tuner plugin towards the bottom displays around +8 cents for the pitch-oriented approach, and a perfect 0 cents (right on tune) for my plugin’s frequency-oriented approach. Both sounds are simple reesed sine waves with distortion so that the Tuner plugin can detect the upper harmonics.

If you’re interested, the source code is available on GitHub. I’ve also included the VST3 in the “Releases” section if you want to play with the plugin in the comfort of your own DAW.

Please make sure to also check out the WolfSound YouTube channel; I used one of his fantastic JUCE tutorials as starter code for the project.

references

https://splice.com/blog/reese-bass-history/ — A brief history of the reese bass.

https://juce.com — The C++ framework I used to develop the plugin.

https://thewolfsound.com/sound-synthesis/wavetable-synth-plugin-in-juce/ — The tutorial I followed to generate the starter code for the project.